Originally posted 4/7/09. Updated 8/23/16.

It’s a ballsy move to remake your own movie. In a way, it expresses the fact that the first rendition of the film was flawed. Yet there’s also a courageous side to this as well; admitting that the film needed to be remade to get across the point the director was trying to make is a step towards dedication and perfection, as a writer may strive for with his milieu of rough novel drafts.

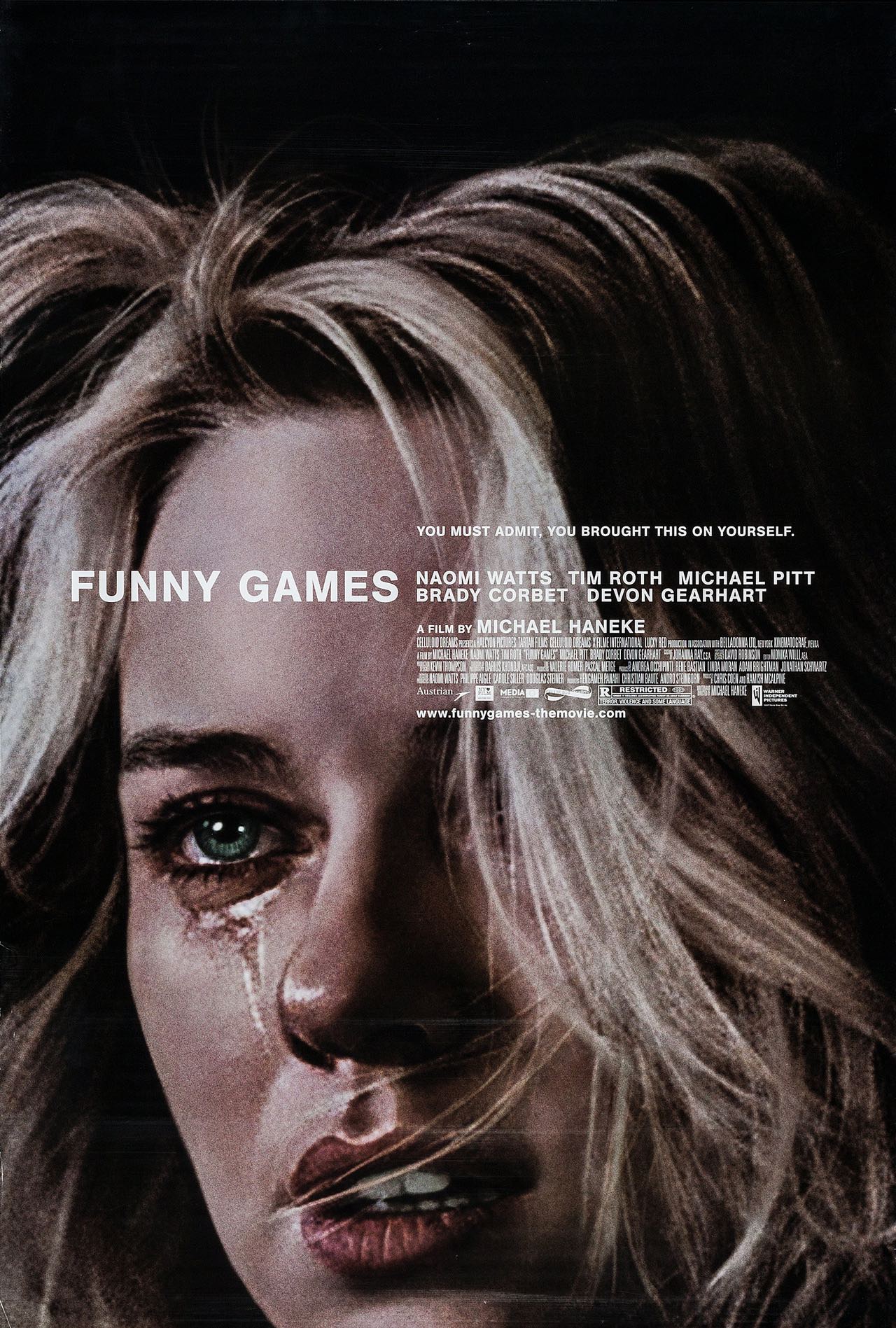

This is, then, part of the reason for director Michael Haneke‘s remake of his own film, Funny Games. While I’ve never seen the original, I can safely conclude that this 2007 rehash is a successful attempt at creating Hanek’s original story that can stand on its own without having to know the background of the films.

A rich, collected family of three travels to their summer house on a secluded resort, consisting of mother Ann (Naomi Watts), father George (Tim Roth), and son Georgie (Devon Gearheart). They are immediately characterized as laid-back, golf-vest-and-khaki-pant people who live for the finer things in life because they have the money to. Yet as they move in to their home, Ann and George notice strange things about their neighbors. Two new boys have shown up, Paul (Michael Pitt) and Peter (Brandy Corbet), both of whom seem to harbor some strange qualities. The family tries to get settled into their home, but the two boys come over asking for some eggs. Instead, Peter and Paul make themselves comfortable at the familiy’s house, playing little games with the family that terrorize them without much actual violence. They make a bet with the family – Paul and Peter wager that the family won’t make it to 9 AM the next morning while the family bets they do.

Right from the beginning, things seem strange within the movie world. There are quick, abstract shots of the family driving in the car, listening to classical music, and director Haneke does a great job of showcasing how boring and stereotypical the family we are about to follow is. Soon, a great noise/grind track by John Zorn’s band Naked City takes over the sound, and it comes as a huge shock after the pleasant classical music from before. This fantastic opening gets the audience ready for the terrors that will soon befall the family, and Haneke’s ability to grab the viewer right at the beginning with an unnatural use of sound is so great that I was immediately absorbed in the film.

As the family unpacks, we get strange feelings. Sure, the family seems perfect in every way – yet there’s a weird distance between the parents and the child. At one point, Georgie asks for a knife, and Ann expresses, “I’d like to see that back,” as if she doesn’t trust her son. Father George mimics this by getting pissed at Georgie for scraping up his boat; the parents worry so much about material possessions, which they can obviously afford to buy again, that they push their son away. This plays into the film so much in so many ways that one can’t help but marvel at the subtle characterization expressed in just the opening scene of the film.

For one thing, when the family first meets Paul and Peter at their house, Ann treats them like crap. They want to borrow eggs, and after Peter drops the first batch, Ann begins to verbally insult him with every little thing he does. Here, we see that Ann is quick to judge, especially after Peter knocks her phone into the dish water. From there, everything goes downhill for the family as Paul and Peter start to dish out the torture. In a way, Haneke emphasizes the fact that this family had it coming with slight vengeful tones. It’s harrowing, because we are torn between two points of view: Peter and Paul are awkward, strange fellows but seem to mean no harm in the beginning while the family seems to be more of the enemy. Haneke quickly turns the table, but there’s still a resonance that the family has an inner turmoil as well as the one that Paul and Peter cause.

Another interesting juxtaposition in the film is the two feelings that we get from the two psychotic men’s games. In a way, they are funny, and it’s a horrible feeling that we as the audience get for laughing at the black comedy underneath it all. Take, for example, a scene where Ann is forced to play Hot or Cold to find their dead dog – the situation is not funny at all, yet the way she is led around by Paul is dark, viscious, and comedic all at the same time. There’s this constant battle of emotions in the film that really causes the viewer’s discomfort as we watch helplessly.

The games get progressively more horrible, leading to a climax (for me at least) where Ann is required to fully undress. There’s no graphic depiction of the nudity, nor is there very much onscreen violence, but it makes it all the more brutal to watch Noami Watt’s tears fall as Paul and Peter demean her. This psychological pummeling is a staplepoint for the whole movie, and as we near the end of the film, it’s almost too much.

As I said before, there’s very little graphic violence on screen, and most of the time Paul and Peter don’t physically harm their prey. In this way, it keeps the movie from falling into the cliched torture porn genre – while violent torture is gruesome, it’s rarely afflicting like Funny Games’ realistic terrorization.

There’s another factor that adds to the terrifying realism and claustrophobic atmosphere of the film, too: long camera shots. Some scenes are actually painfully long, with shots being carried out for maybe ten or fifteen minutes. As a culture that is obsessed with constant movement, these scenes are hard to watch not only because of the events happening onscreen but because we aren’t used to the turtle-like crawl of the film. It’s not a flaw, though; instead, it mimics the action of the film. A terribly disturbing scene where Georgie has been killed shows a wide shot of Ann bound in her bra and underwear hopping frantically. At this point, we don’t know who is dead, though it seems it might be Georgie; we think Ann will hop over to Georgie and cry for him, yet instead she hops to the television and shuts it off without even thinking twice of Georgie. There’s an insurmountable amount of tension that this long shot creates – my heart was beating probably three times as fast as I waited for the unforeseeable.

Though it seems Haneke was going for a critique on television as theme for the film, it doesn’t seem strong enough to me. In fact, I feel like Haneke criticized something else entirely – our vengeful spite towards everything. The only violent death we see onscreen is Peter’s, and we feel a relief as it happens. But Haneke rewinds the scene for us so that it never happened, creating this sinister mindset that what we just thought was part of the same thought processes that Paul and Peter have when choosing their victims.

This film is unbelievable, gut-wrenching tension. The long shots might not be for everyone, and the experimental filmmaking like the Naked City song may annoy some, but for those who appreciate the more avant garde, Funny Games is a twisted, painful experience. It’s not for the light-hearted, and it will make you feel disgusting. But then again, Haneke gets that point across undeniably. And while it does resemble A Clockwork Orange to some extent, Funny Games extracts itself from being categorized into any one cliche.